Don’t Panic! Elsevier’s #OpenAccess policy is not malicious

18 August 2014

Yesterday, I noticed a comment on Twitter where Erin McKiernan expressed confusion over Elsevier’s Open Access policy:

Q: Have you seen an exclusive license requirement on open access publishing agreements? Surely not BOAI compliant. @MikeTaylor?

— Erin McKiernan (@emckiernan13) August 16, 2014

This was promptly jumped on by other Open Access advocates, who were insisting that it is “not OA”, “nasty”, and even “malice”:

@MikeTaylor @emckiernan13 By definition that is not OA.

— Charles Oppenheim (@CharlesOppenh) August 17, 2014

@krisshaffer @CharlesOppenh @MikeTaylor Yup. Nasty, isn’t it? And they aren’t the only ones doing it. Really should be actionable, I think.

— Erin McKiernan (@emckiernan13) August 17, 2014

.@emckiernan13 @CharlesOppenh WHAT THE ACTUAL F*&£ They’ve now crossed the line where this can’t be written off as ignorance. It’s malice.

— Mike Taylor (@MikeTaylor) August 17, 2014

I burned through a few dozen tweet yesterday trying to convince Erin, Mike, & Charles that the exclusive license isn’t a problem for OA at all. This is particularly important because (as of Aug 18) Erin has incorporated this criticism into an Open Letter to the Society for Neuroscience regarding the new Open Access journal, eNeuro, which uses the same licensing scheme (my own emphasis added):

Our first concern relates to the copyright policy of eNeuro. The journal’s policy states that authors will retain copyright but must grant the Society an exclusive license to publish. An exclusive license is in conflict with the tenets of open access, as defined by the Budapest Open Access Initiative (BOAI), and does not reflect the aims of the Creative Commons licenses to allow reuse.

The problem here is that the exclusive license is something that you (the author and copyright holder) grant to the publisher. It is a guarantee to them that you will not take your original content elsewhere. Alone, this would indeed be sketchy, but since both journals turn around and release the article under a CC license, anyone (including the author) can reuse and redistribute the article subject to the terms of the CC license*.

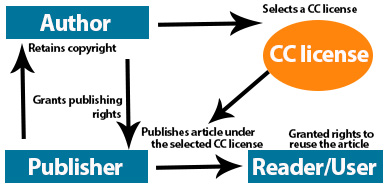

Elsevier’s author agreement actually illustrates this really well:

You grant the publisher exclusive publishing rights then they release the paper under the OA-compliant CC license. There is no adverse impact on the Open Access goals. It is entirely consistent with the Budapest Open Access Initiative. The limitation that it does place is preventing a line directly from the Author to the User. This can actually be useful, as I’ll explain soon.

Above, I used a photo by the very kind-hearted Dustin Gaffke, who shared his photo of Panic! At The Disco on Flickr with a CC-BY license. Thus, I was able to download the photo and upload it here with the proper attribution (noting the copyright holder and providing a link back to the source). This is how the CC-BY license works. I can do all kinds of things with his photo… I can make money off of it, printing it on T-shirts and sell them in the alley outside of Panic! At The Disco concerts, as long as I print “photo by Dustin Gaffke”. I could modify the photo, add my own color effects, mash it up with other photos to make my own Creative Work. Just gotta note the original creator and how it was modified. This is how the CC-BY license works.

However, Dustin is still the copyright holder. He can still do whatever he wants with photo. Maybe Panic! At The Disco likes his photo so much they want to use it for their own promo materials but they don’t want to have to remember to add the proper attribution every time they put it on a mug or poster or concert flyer. He could grant them a license to use the photo without his name (something I can’t do).

Now, the CC-BY license works the same for scholarly works. Releasing under CC-BY doesn’t just let other people read your work without having to pay, but it allows them to redistribute and reuse it. This led to a bit of a kerfuffle last summer, when some scholars realized that their freely downloadable CC-BY papers were getting compiled into textbooks that were being sold for $100+. Now, this anger was largely due to a misunderstanding of what is permitted under CC-BY, but there were some instances where the CC-BY license may have been violated (e.g. poor attribution by omitting a link to the original article and changing the title without noting that the work had been changed). However, we’ll probably never know whether the more dubious practices of Apple Academic Press actually violated CC-BY because they probably will never go to court. Here’s why:

Lets assume for a moment that we see a similar scenario that would be an egregious violation of CC-BY… a textbook gets printed with entire chapters lifted directly from published papers without any attribution for the original author or manuscript whatsoever.

The only way to enforce licensing is litigation, so who sues?

That burden falls on the copyright holders, i.e. the authors of the manuscript. The publisher of the CC-BY paper can’t really do anything to enforce the CC-BY because the original authors (who still have copyright) could have very easily licensed the material to the textbook publisher, as it is wholly within their right to do so, just as it is within Dustin’s right to sell rights to the Panic! At The Disco photo.

Because of this issue, the publisher doesn’t have a case. I would also guess that the academics probably don’t have the time/money/wherewithal to hire lawyers.

However, if the authors have granted an exclusive license to the publisher as Elsevier and the Society for Neuroscience require, they are guaranteeing to the publisher that they will not license the work to anyone else. The publisher can then distribute the work with the CC-BY license. The exclusive license between the copyright holder and the publisher in no way restricts, modifies, or changes the CC-BY license.**

What the exclusive license does allow, though, is for the publisher to pursue legal recourse in the event of a CC-BY violation. They know that (a) they have an exclusive license from the copyright holder and (b) they distributed the work under a CC license. Remember how there is no direct line between the Author and the User in Elesevier’s handy flowchart? So if the work shows up somewhere without attribution, it is obviously a violation of the CC license. The only additional restriction here imposed by the exclusive license is on the author, who must now conform to the CC-BY license as well. They can no longer stick excerpts into a textbook chapter without attributing the original paper.

Is it confusing? A bit, but Elsevier’s Author Guidelines lay it out pretty clearly.

Is it necessary? Not strictly.

Is it helpful? Yes, in at least one scenario.

Is it still OA? Yes.

Is it “malice”? Absolutely not.

n.b. If you are an IP lawyer, feel free to correct me on any of this.